Part I of this post can be found here.

More good luck

In the late 1970s, a lady who lived in my apartment building told me that her boyfriend was also a jazz musician and would soon be moving into the building. I was stunned when she mentioned the name Red Rodney (his bio can be seen here). Red was a trumpet player from Philly, who had played and recorded with the all-time genius of modern music, Charlie Parker. Red had quite a colorful history and many stories abound.

He was kind enough to let me sit in with him on several occasions.

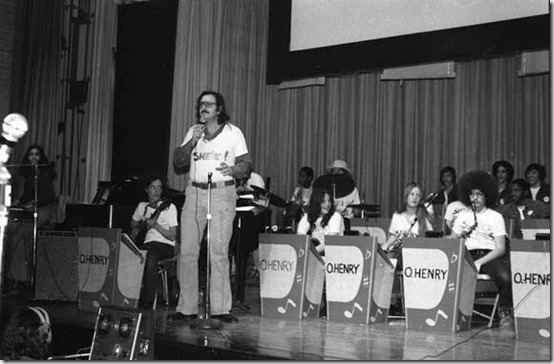

Clark Terry

In late 1980 I heard from some other musicians that the great trumpeter Clark Terry (of Count Basie and Duke Ellington fame) was putting together a big band to go on the road. I obtained contact information for Clark’s manager who was handling the tour, and much to my surprise, the requirements were not purely musical. In addition to a recent recording, you had to submit a photograph.

Hmmm.

What’s that you say?? Hardly a “double-blind” audition? Something’s not quite right with that. You didn’t have to be Albert Einstein to figure out what was going on here. Clark Terry is African-American, and he wants to make sure that he has African-Americans in his band.

Perhaps the photographic requirement was related to the fact that despite being a creation of African-American culture, by 1980 Jazz had largely been abandoned by young African-American listeners and players.

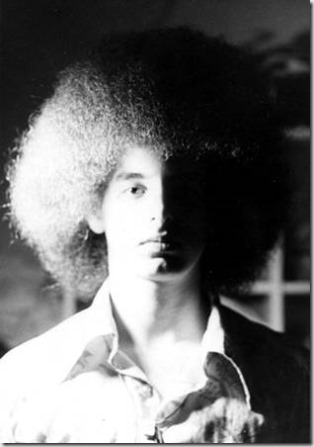

I asked a friend to shoot a Polaroid (seriously dating myself, I know….) so that I could include it with the recording I planned to submit. But – before he snapped the photo, I reached back in time for the hair style I had in the mid-1970s – a mammoth, black-hole-like AFRO. We dimmed the lights, and he clicked the shutter.

The photo and recording were sent to Clark’s manager, and I was quite surprised to receive a call to join the band. It was a nine-week tour starting in February of 1981: three weeks in Europe, six weeks in the USA.

When we got to Europe, Clark went to lunch with some of the other band members, and told them: “I could have sworn that mofo Ned Otter was black, I picked him myself!”

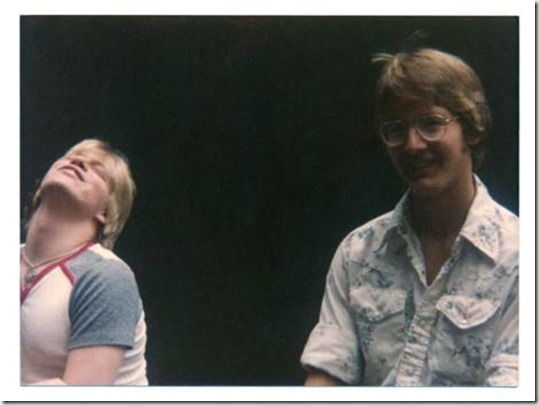

That tour included Branford Marsalis on alto saxophone (he didn’t even own a tenor saxophone yet). To say that Branford and I were outspoken in our disapproval of Clark’s not-so-unique-to-jazz version of creative financial accounting would be an understatement.

Road Warrior

Chris Woods was a friend of Clark’s and a great alto saxophonist, but had the unfortunate task of being the road manager for us wild young folk.

After complaining about something, we would get the party line from Chris. One day, he ended his remarks with “And that’s all you need to know.”

That phrase would reverberate around the bus for the next nine weeks.

Branford and I would often recreate the events of the day, with extra helpings of outrageous mockery. It went something like this:

Me: “Hey Branford!”

Branford: “Yeah, man, what’s up?”

Me: “Look man, I’ve got a gig for you –”

Branford: “That’s great, man. Details please….”

Me: “Well look, it’s like this – first, we parachute into Zimbabwe…”

Branford: “Ok!”

Me: “We drive for 10 hours, do a sound check, then we do the gig –”

Branford: “Beautiful!”

Me: “Then, after the gig, we drive another 10 hours (no dinner), and uh…oh yeah, I almost forgot….that’s right…we have an unscheduled TV show….I don’t know how that slipped into the schedule…fancy that! But in exchange for the unscheduled TV show (which by the way you’re not getting paid for), we’ll be covering your hotel co-pay for tomorrow night”.

Branford: “Fantastic, man, I’m just happy to have a gig! Can’t wait!”

Me: “And that’s all you need to know–”

And it went downhill from there.

Loyalty

On the bus, there was always a clear delineation of loyalty. The booty-kissers were all up front with Clark. The in-betweens were in-between. And the trouble makers were in the back with Branford and myself. After our daily mock-a-thon, you could actually see the steam start to rise up out of Clark’s ears.

I figured that if I was going to be exploited, there was no reason I had to be quiet about it.

One night, Branford – who at least back then was a devious sort of fellow – switched the valves on Clark’s trumpet in between sets. But Clark was such a great trumpet player, he somehow managed to keep playing (I’m sure it required an effort worthy of Hercules).

Another time, Branford and I conspired to play a trick on the vocalist in the band. She was featured on “A Tisket, A Tasket”, made famous by Ella Fitzgerald, and after she sang the opening melody, it was Branford’s turn to solo. But we decided to change things up a bit. Branford stood up to play, and sort of mimed as if he was playing a solo, but I had the microphone passed down my way. The sounds that emanated from my horn would have made Albert Ayler sound like Jelly Roll Morton. The vocalist looked back in horror as Branford tried to keep from falling over with laughter.

Ahh..the Baptism of the Road.

Dizzy Gillespie

In 1988, I got word that Dizzy Gillespie was organizing a big band tour. One of the saxophonists who did the same tour in 1987 and was slated to do it in 1988 – had an opportunity to join a different ensemble that would give him more solo space. This created an opening in Dizzy’s band, and I sent a package to the musical director.

That guy threw my package into the large and ever-growing pile of packages that he had already received, never opening it. Rather than listening to them, he simply called George Coleman for a recommendation. George mentioned my name, and the guy said, “Yeah, I’ve got a package here from Ned Otter”. George suggested that he listen to what I’d sent, and if he liked what he heard, to give me a call.

I was very fortunate to be able to play with Dizzy Gillespie on that tour in 1988. We played Carnegie Hall in New York, Albert Hall in London, massive amphitheatres all throughout Europe, and even went to Istanbul. I am greatly indebted to George for referring me.

in Europe with Dizzy Gillespie, July 1988

(somber faces due to rain delay….)

Further studies

George Coleman mostly performed with a quartet/quintet, but in the early 1970s started an octet. He wrote a lot of the arrangements for this ensemble, but there were contributions by other great musicians as well. In 1996 I produced a recording of George’s octet, and got bitten by the arranging bug myself. My first effort was an arrangement of “Tenderly” – it took six weeks, day and night trying to get it together.

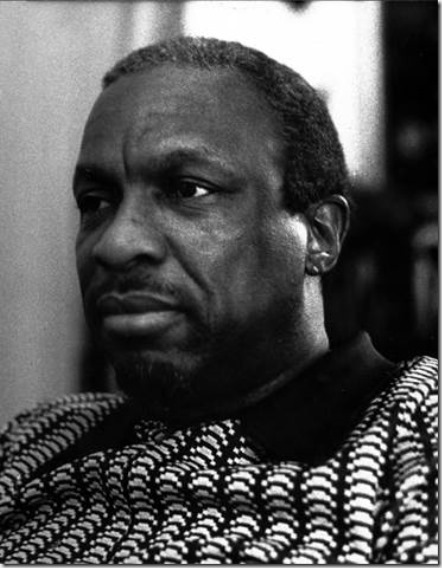

I poured over the existing arrangements in George’s octet book. Among others, there were contributions by Harold Vick, Frank Foster, Frank Strozier, George Coleman, Harold Mabern and Bill Lee (father of renowned filmmaker Spike Lee).

Bill Lee’s offerings were unique – they had a quality that was different than any of the others. I had met Bill years earlier at his home in Brooklyn, when George and I passed through one time.

And so I thought – why not contact Bill Lee for some lessons on arranging and composition? Beginning in 2000 I studied with Bill as often as possible for about a year, and it revolutionized my approach to music. I can say without reservation that Bill Lee is one of the greatest musicians that I have been fortunate enough to be around.

Coda

More than 50 years have passed since there has been a period of great jazz innovation.

Some say that it’s due to the (dis)-integration of the African-American community, that the melting pot of an essentially closed community gives birth to these types of culturally significant seismic shifts.

I’m not sure what’s at the root of it, but I can’t help but think that the chart on this page has a lot to do with it:

The USA is at the top of the television viewing hierarchy, weighing in at a whopping 293 minutes per-person on a daily basis. That’s almost five hours daily, thirty-five hours weekly.

The jazz clubs that were prevalent in all urban environments have all but disappeared. Even New York City – the supposed Mecca of Jazz – has but a handful of clubs left, and a significant portion of those are tourist traps.

Jazz and classical music suffer from the same type of issues: lack of exposure for new audiences. To paraphrase great pianist Barry Harris: “people don’t like jazz but never really heard it…” I think exposure to jazz would have a positive effect on a significant percentage of young people.

Thanks for reading –

Ned Otter

New York City, 2014