Music is my first love – it is an unparalleled force of auditory seduction. Without equal in its ability to bridge cultural, political and geographic divides, it is a union of the unspoken, lyrical and rhythmic aspects of sonic vibration.

No disrespect intended to any lyricists, but lyrics by their nature are limited to what humans can express in words. Perhaps it’s because I am an instrumentalist, I relate directly to the most powerful musical force: the melody.

Many have transcribed and studied the musical notes that great jazz musicians play. However, throughout those classic performances, many other facets of music wash over the listener, which in totality have a powerful effect on the perceived musical experience. A majority of those facets cannot be embodied by any known means of symbolization.

I am so grateful that I have alternate means of economic survival outside of music (see my technology post here). This has allowed me to be true to my music, and avoid the “music as a job” approach that a lot of musicians have to deal with in order to simply survive.

Musical ancestry

While attending school during his early years, my father had been a member of the “color guard”. He was one of the few who was chosen to carry a flag during special activities, and the role was coveted. But there was a problem. Someone – they weren’t sure who – was throwing the entire vocal ensemble off key. They tracked it down to my father, and told him that if he wanted to continue carrying the flag, he would have to stop singing. He had to mouth the words to the national anthem from that day forward.

Bob Otter was absolutely, unequivocally, one hundred percent tone-deaf (luckily he pursued the visual realm, documented here).

Next generation

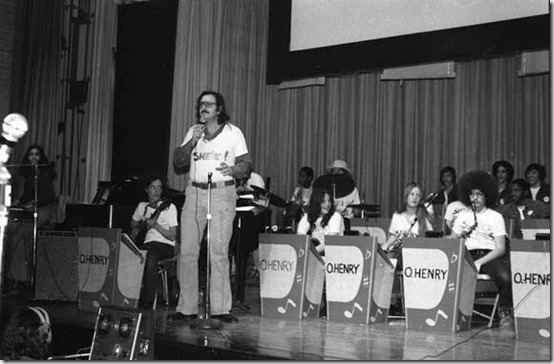

My brother Sam was the first saxophonist I ever saw perform.

In 1970, he played the Paul Desmond classic “Take Five” with the concert band at I.S. 70 (Intermediate School, for those of you not familiar with public school abbreviations).

It was as if I was struck by lightning – I decided at that moment to become a professional musician, despite the fact that (other than kid stuff on a piano) I had never touched a musical instrument. I had no idea if I had any aptitude for things musical.

First mentor

I followed in my brother’s footsteps and attended I.S. 70. It was a fairly new school, and had a large group of young and dedicated teachers. One of them was a tireless motivator, a ceaseless source of musical inspiration: band director Jerry Sheik taught generations of us young folks how to play and appreciate music.

Sheik was not your typical middle school band director. He was a professional musician – a drummer – and had personal relationships with many great musicians of the day, among them Tito Puente. Sheik was my first musical mentor, and as such, he occupies a special place in my musical lineage.

In my last year at I.S.70, Sheik selected a few of us to be members of his “sign-out” crew. Young students who could not afford to purchase musical instruments could take instruments home from Sheik’s band room, and it was our job to keep track of it all. As a member of Sheik’s sign-out crew, we had access to him more than the other kids. After regular school hours, he sometimes played records in the band room, introducing us to new music. One day he was spinning a record that included Cannonball Adderley’s performance of “The Song Is You”, and I asked him who the record belonged to. Seeing how captivated I was by the music, Sheik replied: “You!”, and insisted that I keep it (it is a part of my record collection to this day).

Five days a week, three years running, Sheik was part of my world. While in his care, I developed a deep and infinite love of all things musical, particularly jazz. As Sheik’s musical palette was extremely diverse, we played all types of music. Perhaps because it was also the height of the disco era, I developed a permanent dislike of music of a flippant and/or purely commercial nature.

Jerry Sheik, Musical Mentor Extraordinaire, 1974

photo by Robert Otter

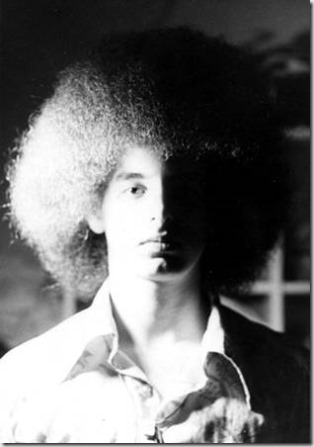

Me – One Funky White Boy, circa 1973

My brother Sam Otter died of shock after taking this photo

Not a natural

I would imagine that my entry into instrumental music was not dissimilar to others. Learning to read and notate music was fun and exciting, but learning to play a musical instrument was slow and frustrating. My ears were way ahead of what I could execute, and at times, my parents would beg me to stop practicing. The endless repetition, the going-nowhere-no-matter-how-many-times-you-tried-to-push-forward – it all added up to a glacially slow and often tortuous path towards improvement (I will confess that a few years later, still struggling to develop technique on the alto saxophone – many, many times did I have the window to my 6th floor apartment open, seriously contemplating whether or not to throw my horn out like a Frisbee…).

Between the ages of eleven to thirteen, the main focus of my life was to advance my musical skills to a point where I might gain entry to “Sheik’s Freaks” as the I.S. 70 Stage Band was known.

Sheik had a friend named Jay Dryer who coached me for my audition to the High School of Performing Arts (known by those who attended simply as PA). I was accepted to PA, which was the school that the movie “Fame” was based on (and no, we did not dance on the cars at lunch time….). Attending PA exposed me to a higher level of musicality than I had been accustomed to. We had sight-singing for an entire year, and that class radically altered the way I heard, recognized and identified different notes.

Students came from all over NYC to attend PA, some from as far away as Staten Island. At the end of my junior year, my friends started talking about this young saxophonist they knew that would be arriving at PA the following year. I got so sick of hearing about this guy, I couldn’t stand it anymore. He was only fourteen years old – how great could he be?

I literally could not believe my ears, when I heard the object of their praise – a brilliant young musician named Drew Francis. He had it all – perseverance coupled with improvisation, composition and arranging skills (and just to add insult to injury – he also had perfect pitch). In addition to saxophone (soprano, alto and tenor), he was an excellent flute and clarinet player. At just fourteen years of age, Drew Francis was light years ahead of anything I could possibly wrap my brain around at that time.

Drew used to make recordings in the basement of his Staten Island house, and one of them included a mutual friend named Dan Weiss, who kindly supplied me with this recording of Drew. It was made when Drew was still a teenager, probably about seventeen.

Sadly, the brilliant light of Drew Francis did not shine long. He passed away at just 39 years old, never having realized a fraction of his great potential.

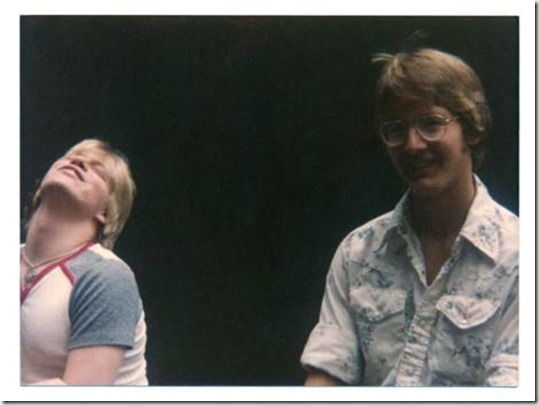

Drew Francis (left), Randy Andos (right)

(photograph by David Rothschild, used by permission)

Second mentor

One crucial development that arose out of attending PA was meeting tenor saxophonist Jeff Gordon. Jeff had a younger brother that attended PA, and he urged me to study with Jeff. By this time I could read and notate music well, understood the basics of harmony, and was a good instrumentalist, given the relatively few years I had been playing the alto saxophone. However, I knew nothing of improvisation. I would go to jam sessions and play transcriptions of other musician’s solos. After my performance of the transcribed solo ended, I was not able to contribute anything of my own.

With regard to studying with Jeff Gordon, I wanted to “try before I buy”, and so in 1976 I attended a concert where Jeff played as part of a larger ensemble. “Blown away” would be an apt description of my reaction. At twenty-two years of age, Jeff was a young lion, bursting with musical feeling. He had everything I coveted.

While continuing to play alto at PA, at seventeen I acquired a tenor, and began my studies with Jeff. After about a year, Jeff informed me that my studies with him were complete He said that I needed to seek out musicians who could take me to the next level, and the two names he mentioned were Frank Foster and George Coleman. I had heard a little bit of George Coleman on Miles Davis’ classic “Four and More” album, and Jeff had also played for me George’s great solo on “Have You Met Miss Jones” from a Chet Baker album.

Sad as I was to move away from the musical sphere of Jeff Gordon, I picked up the phone and called Frank Foster to see if he would take me on. Frank said he was too busy, and was not accepting students at that time.

Right place, right time

Right around this time, I received a phone call from an old friend that I had known at I.S. 70, Josiah Weiner, whose father had a truly unique talent – he could fix any type of art work. We’re talking about art objects that resides in museums and personal collections. As such, the elder Mr. Weiner knew many, many people in the art world, and one of them was Merton Simpson. Mert was one of the foremost dealers of primitive art in the world, and also a tenor saxophonist and jazz fan.

Josiah was calling to tell me that Mert was throwing a party at his gallery at 80th and Madison, and that there would be jazz musicians performing. Knowing of my interest in Jazz, Josiah asked Mert if I could come up and play. Mert agreed.

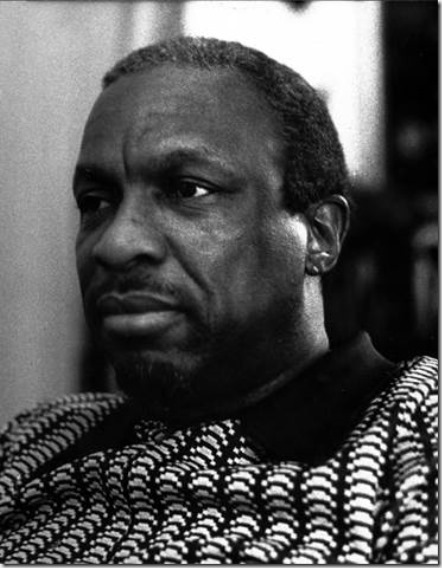

Mert Simpson

photographer unknown

I arrived at the gallery and listened for the first set. Then the musicians asked me to come up and sit in. There was a saxophonist, trumpeter, and a rhythm section. Muscles bursting everywhere, the saxophonist looked like a football player – think “Iron Man”. I remember that I only knew two of the songs they played: “How High The Moon” and “Body and Soul”.

After the set, I walked up to the saxophonist and thanked him for letting me play. I asked him his name, and he replied:

“George – George Coleman…” (this was about two weeks after Jeff Gordon suggested that I study with him).

I picked my jaw up off the floor, ran over to Josiah, and called him every kind of curse word that I could think of for not telling me that I was going to be sitting in with the great George Coleman. Josiah’s response: “Who is George Coleman????”

And so began the longest and most profound musical and personal relationship of my life. I studied with George monthly for about five years. He performed quite often at that time, and I recorded his live performances (still have my cassettes!). At my lessons we would play the recordings back, and I’d ask him about specific things that I didn’t understand.

Many, many pearls of wisdom were imparted at these lessons. But the most precious gift I received was that he taught me how to teach myself. Without fail, all of the musicians that I have known from his generation would never tell you how to play. They might show you an example of one way to do something, and then ask you to continue it.

George Coleman, NYC c. 1980

photographer unknown

University of the Streets

A critical part of my musical education was the time spent around George Coleman and his brilliant band members in between sets, in the back rooms of jazz clubs in New York City. This accumulated hang time, combined with the band stand time that he generously granted me, made all the difference in the world in my musical development. I sat in often, and therefore got to play with and know many of the great musicians that George was associated with. A short list would have to include:

Jamil Nasser, Harold Mabern, Hilton Ruiz, Mario Rivera, Ray Drummond, Billy Higgins, Danny Moore, Al Foster, Walter Bolden, Ahmad Jamal, Junior Cook, Frank Strozier, Harold Vick, Philly Joe Jones, Billy Hart, and many, many others.

I was trespassing in the rarified air and I knew it.

An unexpected phone call from an old friend had positioned me in the exact time and place to encounter one of the all-time great saxophone stylists. George Coleman became my most influential musical mentor, and foster-father. His effect on my musical development is undeniable.

There will be another section to this post.

Thanks for reading –

Ned Otter

New York City, 2014